The Bayeux Tapestry was made approximately ten years after the Invasion and hung in the consecration of Bayeux Cathedral in 1077. The Council of Arras had recommended in 1025 that the illiterate masses could better be educated by hanging suitable pictures in churches. Its importance cannot be overstated, because there is some degree of certainty that William saw it in Bayeux. I therefore propose that its accuracy in all respects is not challengeable. It is for this reason I propose that the difficulties faced with its interpretation are solely due to applying the scenes to the wrong locations. All elements of the Tapestry have a logical and solid explanation that links them directly to the site of the landing of the Norman army in Bulverhythe at ‘Pebesellum’, as detailed in the ‘Quedam Exceptiones’.This was interpreted as Hastings by some and ‘Pevensey’ in others. In order to give it authority in the Church in which it was to hang the text titles written on the finished article were in Latin and not French.

Tapestry was made approximately ten years after the Invasion and hung in the consecration of Bayeux Cathedral in 1077. The Council of Arras had recommended in 1025 that the illiterate masses could better be educated by hanging suitable pictures in churches. Its importance cannot be overstated, because there is some degree of certainty that William saw it in Bayeux. I therefore propose that its accuracy in all respects is not challengeable. It is for this reason I propose that the difficulties faced with its interpretation are solely due to applying the scenes to the wrong locations. All elements of the Tapestry have a logical and solid explanation that links them directly to the site of the landing of the Norman army in Bulverhythe at ‘Pebesellum’, as detailed in the ‘Quedam Exceptiones’.This was interpreted as Hastings by some and ‘Pevensey’ in others. In order to give it authority in the Church in which it was to hang the text titles written on the finished article were in Latin and not French.

The most remarkable element of the Tapestry is its authentic, traceable pedigree and faithful, cartoon-like descriptions of events. There are many mysterious elements that historians have found impossible to reconcile. However, it can be reasonably argued that the designer was so absolutely exact in relation to clothing and events, there seems little doubt that these issues fade away once you understand exactly where the Invasion and Landing took place.

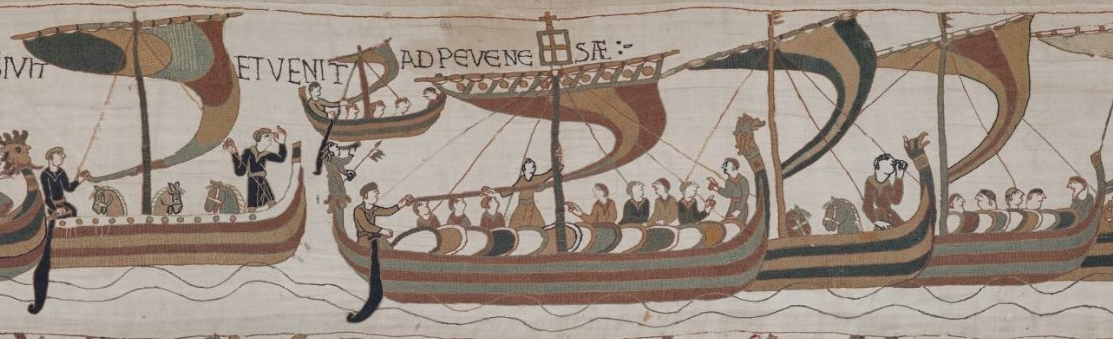

William is shown in the largest boat in the center of the crossing the channel scene. Above in Latin is the text; ‘Et venit ad Pevensae’ which translates in full as:

‘Here Duke William crosses over the sea and came to Pevensey’

As we have seen research fails to find any evidence that the fleet landed at Pevensey town, other than reports from those who did not attend in person generated at least 150 years after the Invasion. So what did the seamstresses mean when they wrote this above the main scene pre-Invasion. Ms Tyson, who has a lot of experience translating Norman documents makes an astute note in her translation of another document, written shorty before called the ‘Carmen of Hastings’ in footnote 23, which also names Hastings as the landing site. She says:

‘William’s first conquest was the neighbouring county of Maine in France which he joined to Normandy in 1062.…The Norman conception of geography identified land by reference to its overlord. St Valery-sur-Somme (where the fleet left from) is identified in line 28 as the ancient port of Vimeu’. Vimeu identifies a region or barony in Normandy rather than a town.’

The text at the center of the crossing the channel scene therefore is a cultural translation issue, in which we are told that the fleet ‘landed at Hastings’ in the next sequence. It shows the horses disembarking from the ships, which ‘landed together’ with all ‘moored side by side’. To the French this meant that the fleet were going to the region of Pevensey, because Pevensey was the region. There was no misunderstanding, because the text is absolutely clear at the landing scene showing they landed ‘at Hastings’.

There  are other issues that specifically put the Normans on the beach at Hastings port in the Bayeux Tapestry. This includes showing two forts (in the plural), one at the top of the hill where they land and one at the bottom, where they dug a ditch. It shows the specific elements of reusing the wood from the boats, which have been dismantled according to Wace, as one of the first jobs done.

are other issues that specifically put the Normans on the beach at Hastings port in the Bayeux Tapestry. This includes showing two forts (in the plural), one at the top of the hill where they land and one at the bottom, where they dug a ditch. It shows the specific elements of reusing the wood from the boats, which have been dismantled according to Wace, as one of the first jobs done.

Bishop Odo is then shown eating fish in the Tapestry, whilst the rest of the party eat chicken. This can only have meant that the party were on the beach at Hastings on the Friday 29th September, because there was neither tide nor time to have traveled down the coast to Pevensey and arrive back at Hastings the same day. The custom of men of the cloth eating fish on a Friday was a Christian custom that lasted from the time of Christ until today in Christian religious countries such as Ireland.

Wace covers this in his version of the same events by stating that the Normans went to Pevensey the day after they landed, by way of explanation.

Historians have struggled with a host of issues by trying to make them fit both Pevensey as the landing site and also where the battle was believed to take place in Battle. Every attempt to prove the point failing, because of issues in the text, causing the battlefield and landing site to be lost. Some thought that the landing site had been lost to the sea, due to coastal erosion, unaware that recent geological surveys proved the old town two miles to the east of the old port had no Norman involvement prior to building the current castle (1090AD).

The fact that the Bayeux Tapestry is a faithful interpretation of all events in the order that they happened has also allowed confirmation regarding the topography of the land, in which the battle took place. The position of the camp at Wilting Manor is confirmed by the sequence in which the Normans march to battle over one valley and one hill to the plain where the battle commences next to the Yew tree with a split down the middle (by Crowhurst Church). The yew being an ancient landmark of the Saxon enclosure where the church is built. The story shows the burning of Crowhurst Manor with a woman (unnamed) and child upon landing, who were undoubtedly Harold’s Danish wife and son. They were known to everyone who attended, yet no comment is found in the Tapestry.

Lastly the detail in the Tapestry shows the trees were landmarks and scene markers, where the detail of what was in their branches identified the start at the port (with water in the tree), to branches containing ploughed land where farm land was crossed. Each element in the land was noted where the rise or fall in the land corresponds precisely to the land over which the Normans traveled down the London Road, identifying a clear link between the battle site at Crowhurst and Wylting, where the Norman camp was based. It is beyond doubt that such detail could be considered another coincidence, confirming the absolute accuracy of the document as well as the camp site and battlefield as confirmed by the Domesday evidence.

The discovery of Wace’s document the Roman De Rou in the library at Battle Abbey confirms the monks at Battle knew and understood the significance of that text as an accompanying text to the Bayeux Tapestry. If you have read the text displayed here you may challenge the conclusions on the blog pages held on Facebook or you may want to visit the site in order to check out how it was possible for every single historian to be misled by the abbot who implemented this fraud. He did not see it as a fraud, because as Elenor Searle commented it could only serve them well in the future. None the less it was not true and you like every historian since has accepted what you were told by experts who should have known better. The mistake was not yours. To insist that your teachers knew best in stating that Pevensey was the landing site is simply to repeat the lies of the past.

Events such as this are we believe unique in English history. They where never meant to do any harm, but by being continued over the centuries harm did fall upon those who followed them. No amount of bluster will convince me and the world at large that the Normans landed at Pevensey, when it is known that the Latin for Pevensey is not Pebesellum, where FitzOsborn noted that the fleet landed. He was given the land involved and had a special reason to make sure his document was right. The correct landing place is in Pebsham and to deny this without even looking on the beach displays an arrogance that does not deserve to exist in the world of History or academia. Similarly the word ‘monimentum’ is the Latin for ‘Monument’ and to deny that the Normans marked their graves, as well as Harold’s, shows the greatest disrespect for the dead who died in the service of their King and country. For this we owe thanks to Artificial Intelligence who drew attention to the error as detailed in the book 1066 The Battlefield.